Mrs. Kitchen’s husband, Dr. Joseph Kitchen was never a formal teacher of mine, per say. However, for three years I served as his assistant in his role as music director at St. Stephen’s Church in Durham, North Carolina. Turning pages of Bach and Widor –Sunday after Sunday– was an incredible education in sight reading, arranging and –believe it or not– the physics of sound. That Flentrop Pipe Organ was a music student's pedagogical dream.

I was further influenced by Nicholas Kitchen, Dr. and Mrs. Kitchen's son. He was a violin prodigy whose dedication to music greatly inspired me (and somewhat intimidated me, as well). The Kitchen's also had a daughter, Julie, whose subtle idea of humor –and intolerance for imperfect tonality– taught this then wired teenager a bit more about patience than I should have liked at that age.

Stephen Jaffe, a composer in residence at Duke –and a protégé of George Rochberg– was my first formal teacher in composition. Jaffe surely considered me an idiot. I'm pretty famous for thinking sideways. Sometimes it works to my advantage; sometimes I come across like an alien life form.

I spent three months in Vermont studying dual compositional studies. Firstly, I had been drawn up there to study computer music programming with a pioneer in the field, Joel Chadabe, via my readings of MIT's Computer Music Journal. It was Joel who sent me off to work for Jonathan Elias –another previous student of his– with his gracious recommendation.

I spent three months in Vermont studying dual compositional studies. Firstly, I had been drawn up there to study computer music programming with a pioneer in the field, Joel Chadabe, via my readings of MIT's Computer Music Journal. It was Joel who sent me off to work for Jonathan Elias –another previous student of his– with his gracious recommendation.Secondly, and quite fortuitously, I discovered Free Jazz trumpeter Bill Dixon living up there, and he shared with me his tremendous insight about both harmony and life. He also endowed me with an ethic that while mistakes are absolutely intolerable, not to confuse them with spontaneous bouts of human expression, which often tear out of the soul in what can only be described as a messy experience.

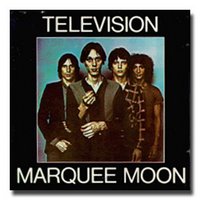

Later in life, after what seemed a lifetime in a recording studio, I abandoned technology for several years in order to reconnect with the simplicity of steel strings, and studied guitar with Richard Lloyd of the legendary band Television. There are teachers and their are wizards. Richard is a wizard. He imparted on me an idea to think less in terms of linear melodic structure, more like a guitarist –fingers and inner ear surfing a three dimensional diagonal navigation across a pitch/emotion axis.

Later in life, after what seemed a lifetime in a recording studio, I abandoned technology for several years in order to reconnect with the simplicity of steel strings, and studied guitar with Richard Lloyd of the legendary band Television. There are teachers and their are wizards. Richard is a wizard. He imparted on me an idea to think less in terms of linear melodic structure, more like a guitarist –fingers and inner ear surfing a three dimensional diagonal navigation across a pitch/emotion axis.It’s also worth mentioning that at nineteen, while in attendance at the 1984 Synclavier II Summertime Seminar, the legendary jazz pianist Oscar Peterson offered this advice to a young musician, which has stayed with me my whole life. He said, “If you want to be a great musician, read –not music, read books.”

No comments:

Post a Comment