As Executive Producer for Blister Media, part of my job includes marketing the company to new breed technology/content companies who create advertising and entertainment for the web. Back in 1998, when we founded the company, I sketched out some ideas for a virtual vision statement, which I'm not sure ever got fully executed. But thought I'd publish some of those initial thoughts here under the guise of an Interactive Audio Manifesto. The title is tongue and cheek, but the bullet points may have some inspirational value–

INTERACTIVE AUDIO MANIFESTO

• Experimentation yields great advances in science and technology; The same is true for art.

• If your ears are hungry, feed them music.

• The consumer is your audience.

• Audiences demand to be entertained.

• They’re not just ‘eyeballs’. They’re eyeballs with brains.

• When given a choice, audiences don’t buy bland.

• Information and Entertainment are most effective when combined.

• Nothing identifies you like your face. Except your voice.

• Audio is most effective when used judiciously:

1. Use it to brand.

2. Use it to entertain.

3. Use it to convey information.

Anything else is wasted bandwidth

Thursday, June 14, 2001

Interactive Audio Manifesto

Labels:

Blister Media,

Interactive Audio

Wednesday, June 13, 2001

Tooting My Own Horn

A company's legacy is the sum of its people. Several years after my departure, Elias offered as part of its promotional literature, several pioneering 'FIRSTS'. Imagine my happy surprise to learn that I was a principle player in at least half of the ‘firsts’.

Among them:

• First to use music supervisors

(I was on the first team of music supervisors)

• First bi-coastal music production house

(I was on the first bi-coastal production team; and created SOP for the production of all in-house music, sound design and sonic branding projects for both the East and West Coast production offices).

• First Olympic music library with Meta tags and digital database

(I was one of three internal supervisors/producers that created that first Meta tagged music library.)

• First commercial music company to do product sonification

(I produced, or was part of a team that produced, the company’s earliest product sonification projects for AT&T and TeleTV)

• First company to do corporate audio identity systems

(I worked on the company’s first corporate audio identity system –with Alexander Lasarenko– which was created for Elias Arts itself!)

* * *

Honestly, who really knows if any of these ‘firsts’ have any historic –albiet narrow– importance within the industry, or if they are all simply bits of a marketing mythology? Hell, I don’t care: it's a mythology business, and if current and future crews of Elias are as proud of the company's legacy, then I couldn't be happier to have made some small contributions to its development. It was a wonderful time with wonderful people, full of art and music and chaos and personality.

Labels:

Elias,

Interactive Audio,

Music House,

Terry O'Gara

Tuesday, June 12, 2001

Every Beat Must End

I worked 361 days of the preceding twelve months before I resigned from the commercial music, sound and audio identity firm Elias Associates, now named Elias Music.

For the previous two years my typical workday started at 8AM and ended between 10PM and midnight. We were so busy and being a one man production department, it was simply the only way I could singularly produce both day and night shifts. Before that, I spent three years taking a nap at 8pm so that I could return to the studio at 2AM, to learn the technology and work on my own projects.

I had attempted to hire an assistant in the past, but after a training period of about six months, one young woman added up the hours and told me in no uncertain terms, "I don't want your job." –And then she quit!

We had four rooms in the New York office alone, three of them running two back-to-back, 12-hour shifts, resulting in at least one national spot going final every 2 or 3 days, -and one room devoted to early interactive audio projects where sound for games and theme park attractions was created.

It was, as '80's retail icon Crazy Eddie liked to say, "INSANE!"

In retrospect I was extremely lucky to make new strategic relationships and enjoy similarly inspiring working collaborations after my departure from Elias, but if I hadn’t, those few years would have made the rest worth it.

I'm especially proud of having had the opportunity to play an executive leadership role as part of a management team that essentially quadrupled revenues over a three year span, and evolved during my watch from an old economy music production house into the leading U.S. Sonic Branding and Sound Identity firm of its time.

Along the way I established Standard Operating Procedures for both New York and West Coast offices; promoted and managed collaborations with Machine Head, a west coast-based sound design company; repaired and normalized relationships with both the American Federation of Musicians and the Screen Actor's Guild unions; and I played a significant role in the a transformation of the company culture by actively and consciously recruiting new creative talent with contrasting talent and skill sets – developing a new paradigm of talent development within the company.

The result was that instead of a having a staff of composers who worked in relative competitive isolation from one another, as had been the case in the past, the company now enjoyed a sense that each project was open for collaboration.

It felt more like a band than a music house, and the diverse artistic perspectives and processes also contributed to the general development of the company's brand image as a creative solution provider, and not just a jingle factory.

Among the new team I scouted and either recommended for hire, or hired directly, were composers Fritz Doddy, Matt Fletcher, Todd Schietroma, Rich Nappi and Kerry Smith; also sales rep Debra Maniscalco, associate producer Jonathan Nanberg, studio manager Jennifer McGee, recording engineer Mario Piazza, and producer Keith Haluska.

I also developed and forged important external strategic creative relationships with many of New York's hottest upcoming young performers then bubbling up under the radar. Among these relationships, notable mentions for their contributions to our creative output must include: Trumpeter Chris Botti, guitarist Eric Schermerhorn, New York Philharmonic violinist Sandra Park, orchestrators Deniz Hughes and Tony Finno, and newly established vocal management firm, Val's Artist Management (aka VAMNATION).

I eventually found my own replacement in a young producer I had worked with a year or two before on a NEC job. Keith Haluska immediately impressed me with how much he loved music, –and the business of music– and so he struck me as a good fit for the company. He started in June '96, dovetailing my final departure by three months.

I suspect the relatively brief time I spent with Keith didn't actually make his job appreciably easier. One hopes, but you can’t wrap up an old role like a holiday package and give it to someone without part of the puzzle missing. All you can do is give them a few of the pieces, and hope they can make something out of it –their own thing. If you can accomplish that, then I think you can finally move away from the stage, back into the wings, out the back door, and into the street, where life awaits, ready to pick up where you left off, and where hopefully it has remained, waiting patiently to tease you with the next big thing.

For the previous two years my typical workday started at 8AM and ended between 10PM and midnight. We were so busy and being a one man production department, it was simply the only way I could singularly produce both day and night shifts. Before that, I spent three years taking a nap at 8pm so that I could return to the studio at 2AM, to learn the technology and work on my own projects.

I had attempted to hire an assistant in the past, but after a training period of about six months, one young woman added up the hours and told me in no uncertain terms, "I don't want your job." –And then she quit!

We had four rooms in the New York office alone, three of them running two back-to-back, 12-hour shifts, resulting in at least one national spot going final every 2 or 3 days, -and one room devoted to early interactive audio projects where sound for games and theme park attractions was created.

It was, as '80's retail icon Crazy Eddie liked to say, "INSANE!"

In retrospect I was extremely lucky to make new strategic relationships and enjoy similarly inspiring working collaborations after my departure from Elias, but if I hadn’t, those few years would have made the rest worth it.

I'm especially proud of having had the opportunity to play an executive leadership role as part of a management team that essentially quadrupled revenues over a three year span, and evolved during my watch from an old economy music production house into the leading U.S. Sonic Branding and Sound Identity firm of its time.

Along the way I established Standard Operating Procedures for both New York and West Coast offices; promoted and managed collaborations with Machine Head, a west coast-based sound design company; repaired and normalized relationships with both the American Federation of Musicians and the Screen Actor's Guild unions; and I played a significant role in the a transformation of the company culture by actively and consciously recruiting new creative talent with contrasting talent and skill sets – developing a new paradigm of talent development within the company.

The result was that instead of a having a staff of composers who worked in relative competitive isolation from one another, as had been the case in the past, the company now enjoyed a sense that each project was open for collaboration.

It felt more like a band than a music house, and the diverse artistic perspectives and processes also contributed to the general development of the company's brand image as a creative solution provider, and not just a jingle factory.

Among the new team I scouted and either recommended for hire, or hired directly, were composers Fritz Doddy, Matt Fletcher, Todd Schietroma, Rich Nappi and Kerry Smith; also sales rep Debra Maniscalco, associate producer Jonathan Nanberg, studio manager Jennifer McGee, recording engineer Mario Piazza, and producer Keith Haluska.

I also developed and forged important external strategic creative relationships with many of New York's hottest upcoming young performers then bubbling up under the radar. Among these relationships, notable mentions for their contributions to our creative output must include: Trumpeter Chris Botti, guitarist Eric Schermerhorn, New York Philharmonic violinist Sandra Park, orchestrators Deniz Hughes and Tony Finno, and newly established vocal management firm, Val's Artist Management (aka VAMNATION).

I eventually found my own replacement in a young producer I had worked with a year or two before on a NEC job. Keith Haluska immediately impressed me with how much he loved music, –and the business of music– and so he struck me as a good fit for the company. He started in June '96, dovetailing my final departure by three months.

I suspect the relatively brief time I spent with Keith didn't actually make his job appreciably easier. One hopes, but you can’t wrap up an old role like a holiday package and give it to someone without part of the puzzle missing. All you can do is give them a few of the pieces, and hope they can make something out of it –their own thing. If you can accomplish that, then I think you can finally move away from the stage, back into the wings, out the back door, and into the street, where life awaits, ready to pick up where you left off, and where hopefully it has remained, waiting patiently to tease you with the next big thing.

Labels:

Elias,

Music House,

Terry O'Gara,

Waxing Nostalgic

Monday, June 11, 2001

Winning Awards with Collaboration and Conflict

During my tenure as the Senior Producer and Head of Production at Elias Arts, an especially productive relationship developed between our Creative Director, Alexander Lasarenko, and myself, whereby Alex considered each opportunity or commission to score a TV commercial primarily as cinematic art (i.e. a potentially entertaining experience in and of itself) –its intent as a vehicle for a brand message or marketing piece –and our budget, notwithstanding.

By contrast, my responsibility was to ensure our client's marketing and message mandate was appropriately represented in our musical and sonic compositions, –and internally, that our creative solutions were executed in a manner that left us with either a profit or a relationship that would produce one later.

-But as a direct result of this contrasting dynamic our ideas and our execution got better, and I think the subsequent award-winning results speak for themselves. -And I can't think of another music team that did it the way we did at the time, which turned out to be so successful, that it made us all feel we were invincible at the time.

And we were a pretty good team! Two years before we were nobodies or newbies.

Now, a year and a half after my promotion to Senior Producer, Elias NY had become the toast of the North East, and was even drawing clients from the west coast and London. In 1996 we walked away with two of three AICP awards in the music category (Guess ‘Mambo’ (Schietroma) and ‘Levi’s Sensual’ (Jenkins)) and a Clio for a Marcus Nispel directed spot out of DDB, produced by Steve Amato, for the Digital Equipment Corp., called ‘Manifesto’.

What made that latter award all the more sweet was the fact that it had been a collaborative effort whose participants included several new composers working in tandem with Alex, Alton Delano, Fritz Doddy, and myself. The year after I left, several other awards rolled in for projects produced during my tenure, including AICP recognition for Levi’s ‘Primal’, composed by Kerry Smith.

Of the many awards the company’s staffers have earned over the years, I take great pride knowing that a creative team I recruited and assembled swept award shows in the mid to late nineties. For a time –when Jonathan Elias headed out west and Scott Elias stopped out to pursue other ventures– those of us who spearheaded the company’s flagship headquarters did a unprecedented job catapulting its capabilities back into national industry notice.

When I started my tenure, the company billed less than a quarter of what it reportedly billed during my last year with the company –according to publicly available records. We quadrupled profits in 24 months and made the Elias Brothers proud. But the awards were icing on the cake, because more importantly, for a shy kid who didn't move to the United States until he was 13, it was a good American dream to have lived, and to have lived it with so many generations and talented individuals.

By contrast, my responsibility was to ensure our client's marketing and message mandate was appropriately represented in our musical and sonic compositions, –and internally, that our creative solutions were executed in a manner that left us with either a profit or a relationship that would produce one later.

This meant when our Creative Director felt strongly about pursuing a creative thread that was not part of the original brief, he would have that conversation with me instead of ‘fighting for the idea’ with our clients, as had been the organization’s prior model. As a result we sometimes did take new ideas to the client, but only after any sense of ‘fight’ had been eliminated from our mindset. In practice, though, now instead of fighting the clients we often fought each other.

-But as a direct result of this contrasting dynamic our ideas and our execution got better, and I think the subsequent award-winning results speak for themselves. -And I can't think of another music team that did it the way we did at the time, which turned out to be so successful, that it made us all feel we were invincible at the time.

And we were a pretty good team! Two years before we were nobodies or newbies.

Now, a year and a half after my promotion to Senior Producer, Elias NY had become the toast of the North East, and was even drawing clients from the west coast and London. In 1996 we walked away with two of three AICP awards in the music category (Guess ‘Mambo’ (Schietroma) and ‘Levi’s Sensual’ (Jenkins)) and a Clio for a Marcus Nispel directed spot out of DDB, produced by Steve Amato, for the Digital Equipment Corp., called ‘Manifesto’.

What made that latter award all the more sweet was the fact that it had been a collaborative effort whose participants included several new composers working in tandem with Alex, Alton Delano, Fritz Doddy, and myself. The year after I left, several other awards rolled in for projects produced during my tenure, including AICP recognition for Levi’s ‘Primal’, composed by Kerry Smith.

Of the many awards the company’s staffers have earned over the years, I take great pride knowing that a creative team I recruited and assembled swept award shows in the mid to late nineties. For a time –when Jonathan Elias headed out west and Scott Elias stopped out to pursue other ventures– those of us who spearheaded the company’s flagship headquarters did a unprecedented job catapulting its capabilities back into national industry notice.

When I started my tenure, the company billed less than a quarter of what it reportedly billed during my last year with the company –according to publicly available records. We quadrupled profits in 24 months and made the Elias Brothers proud. But the awards were icing on the cake, because more importantly, for a shy kid who didn't move to the United States until he was 13, it was a good American dream to have lived, and to have lived it with so many generations and talented individuals.

Labels:

Artists and Repertoire,

Elias,

Music House,

Terry O'Gara

Sunday, June 10, 2001

Artists and Repertoire for Madison Avenue

Music and sound design production houses which specialize in the delivery of non-entertainment audio projects often draw a creative boundary between the composition and production departments.

The fact is, a music house is a post-production facility. Composers score tracks, and producers bridge the gap between project management and sales.

In fact, many 'music' producers in this environment are recruited from advertising agencies or other post houses, and their primary advantage to the music house is not their ability to produce a track, but to produce clients! Indeed, Executive Producers in post are generally leading sales efforts, not managing projects.

Obviously, you'll note how vivid the contrast in comparison to the entertainment model, whereby producers are artists themselves and often expected to be collaborators –an additional member of the band, per se.

As I worked up the ladder @ Elias, it was not simply my intention to develop a career as a project manager, or as someone who could 'run a creative company', but as someone who was also a creative resource. One key advantage I had, which was then unique to the company, was my youth spent growing up overseas, in the Caribbean, South America, Europe and the Mid East.

As it turned out, I had a very open ear, and as a result I was very good at discovering and directing talent, especially in the genre of what Americans then called 'world music'.

I also discovered in very short order that my 'casting' choices could influence the creative direction of a given track with great effect. It also helped that I enjoyed the casting process. Just like an A&R scout @ a record label, I recruited talent right out of clubs and bars. But I also found singers and musicians busking away in subway terminals and on sidewalks. It shouldn’t come as any surprise that in New York City, many curbside artists are conservatory trained virtuosos –and they arrive from all over the world.

Additionally, I never walked out of an ethnic restaurant that featured a live musical performance without taking every musician’s phone number. Need an Urdu player? I know a guy. I took a lot of pride introducing our composers to authentic players of every variety. When the Tourism Boards of Mexico and The Bahamas each required native talent to perform on their respective campaigns, which we we were commissioned to compose, I was the go-to global guy who connected with embassies and delivered.

I'm particularly proud of introducing our composers to the talents of musicians they may have already worked with about but hadn't fully exploited or explored, because they had never really talked to a specific musician or singer about what they 'really' did. Chris Botti was just another trumpet player in the rolodex until I found out –simply by asking what he did otherwise– that he toured with Sting and Paul Simon and therefore had an ear for improvising around almost any style of music. In short order, he moved from a horn player to our first call on anything we considered esoteric.

I have many stories like this. It's easy to put someone in a niche. But talk to them for a few minutes and a world opens up.

I've learned that the best talent doesn't always arrive on a demo tape with an accompanying electronic press kit. The best talent you discovered –in person– because you went out one day believing everyone has a unique gift, and if you look for magic, you’ll find it.

Today, loops –short repeatable audio snippets– are frequently used in the construction of music. As early as 1991 Elias had a huge library of loops and samples. I myself had been working with loop based composition since 1985, the result of my youthful fascination with the Brian Eno and David Byrne collaboration, ‘My Life in the Bush of Ghosts’. Nevertheless, I always fought hard for using live players and ‘rolling our own’ samples. Even one solo violinist, for instance, over dubbed on an otherwise sampled string section will communicate just enough fractal audio information to fool most human beings into thinking everything they're hearing is 'live'.

Yes, it's cheaper to do it all yourself and not work in the moment with live musicians. And that’s certainly the trend, but we lose something when we stop working together. Of course, maybe the next generation won’t miss it after it’s gone because they’ll never had the experience to compare it to in the first place.

The fact is, a music house is a post-production facility. Composers score tracks, and producers bridge the gap between project management and sales.

In fact, many 'music' producers in this environment are recruited from advertising agencies or other post houses, and their primary advantage to the music house is not their ability to produce a track, but to produce clients! Indeed, Executive Producers in post are generally leading sales efforts, not managing projects.

Obviously, you'll note how vivid the contrast in comparison to the entertainment model, whereby producers are artists themselves and often expected to be collaborators –an additional member of the band, per se.

As I worked up the ladder @ Elias, it was not simply my intention to develop a career as a project manager, or as someone who could 'run a creative company', but as someone who was also a creative resource. One key advantage I had, which was then unique to the company, was my youth spent growing up overseas, in the Caribbean, South America, Europe and the Mid East.

As it turned out, I had a very open ear, and as a result I was very good at discovering and directing talent, especially in the genre of what Americans then called 'world music'.

I also discovered in very short order that my 'casting' choices could influence the creative direction of a given track with great effect. It also helped that I enjoyed the casting process. Just like an A&R scout @ a record label, I recruited talent right out of clubs and bars. But I also found singers and musicians busking away in subway terminals and on sidewalks. It shouldn’t come as any surprise that in New York City, many curbside artists are conservatory trained virtuosos –and they arrive from all over the world.

Additionally, I never walked out of an ethnic restaurant that featured a live musical performance without taking every musician’s phone number. Need an Urdu player? I know a guy. I took a lot of pride introducing our composers to authentic players of every variety. When the Tourism Boards of Mexico and The Bahamas each required native talent to perform on their respective campaigns, which we we were commissioned to compose, I was the go-to global guy who connected with embassies and delivered.

I'm particularly proud of introducing our composers to the talents of musicians they may have already worked with about but hadn't fully exploited or explored, because they had never really talked to a specific musician or singer about what they 'really' did. Chris Botti was just another trumpet player in the rolodex until I found out –simply by asking what he did otherwise– that he toured with Sting and Paul Simon and therefore had an ear for improvising around almost any style of music. In short order, he moved from a horn player to our first call on anything we considered esoteric.

I have many stories like this. It's easy to put someone in a niche. But talk to them for a few minutes and a world opens up.

I've learned that the best talent doesn't always arrive on a demo tape with an accompanying electronic press kit. The best talent you discovered –in person– because you went out one day believing everyone has a unique gift, and if you look for magic, you’ll find it.

Today, loops –short repeatable audio snippets– are frequently used in the construction of music. As early as 1991 Elias had a huge library of loops and samples. I myself had been working with loop based composition since 1985, the result of my youthful fascination with the Brian Eno and David Byrne collaboration, ‘My Life in the Bush of Ghosts’. Nevertheless, I always fought hard for using live players and ‘rolling our own’ samples. Even one solo violinist, for instance, over dubbed on an otherwise sampled string section will communicate just enough fractal audio information to fool most human beings into thinking everything they're hearing is 'live'.

Yes, it's cheaper to do it all yourself and not work in the moment with live musicians. And that’s certainly the trend, but we lose something when we stop working together. Of course, maybe the next generation won’t miss it after it’s gone because they’ll never had the experience to compare it to in the first place.

But if you manage your budget properly, why fake push button to trigger a loop when you can have a famous Brazilian percussionist in your room laying down tracks with a world-renown fretless bass player from Kenya.

Real musicians and singers are also talents in themselves that can add magic to a track. Ask yourself, who would sound cool on that this? Sometimes the answer I can up with was a single member of the New York Philharmonic. I loved calling in David Bowie’s guitarist at the time, Eric Schermerhorn. A lot of guitarists can shred, but few have the fluid cinematic sense that Eric does. You see, it’s not what guitar will add, it’s what Eric will add. Big difference.

Among my few contributions to the company, one of my proudest is simply creating the database of hundreds of uniquely gifted musicians and singers with global talents, some of which were not even ‘professional session players’ until I heard them busking and recommended them to our composers.

Simply consider why a music producer would feel any pride for a track he or she did not compose. Maybe because he or she suggested something or someone to a composer or sound designer, and they acted on it, resulting in an end product that evolved into more engaging experience than either of you could have imagined before.

And in that way, I’m convinced, we all win: clients, creatives, colleagues, culture, the work.

Real musicians and singers are also talents in themselves that can add magic to a track. Ask yourself, who would sound cool on that this? Sometimes the answer I can up with was a single member of the New York Philharmonic. I loved calling in David Bowie’s guitarist at the time, Eric Schermerhorn. A lot of guitarists can shred, but few have the fluid cinematic sense that Eric does. You see, it’s not what guitar will add, it’s what Eric will add. Big difference.

Among my few contributions to the company, one of my proudest is simply creating the database of hundreds of uniquely gifted musicians and singers with global talents, some of which were not even ‘professional session players’ until I heard them busking and recommended them to our composers.

Simply consider why a music producer would feel any pride for a track he or she did not compose. Maybe because he or she suggested something or someone to a composer or sound designer, and they acted on it, resulting in an end product that evolved into more engaging experience than either of you could have imagined before.

And in that way, I’m convinced, we all win: clients, creatives, colleagues, culture, the work.

Saturday, June 09, 2001

From Senior Producer to Creative Producer

The entertainment and advertising industries are both populated with many kinds of people possessing different skill sets, specialties and methodologies, and all of whom wear the title PRODUCER. Depending on their career development, most have learned some degree of project management skills. It would be difficult, I imagine, to actually begin producing a project without knowing how to manage time, budget, resources and personnel. But at one end of the spectrum we have producers whose skill set parallels ACCOUNT or BUSINESS MANAGEMENT; and on the other end we have producers who are purely ARTISTS, and whose skill set, however expansive, may be limited to creative process.

The former excel at managing clients and sometimes process, but do not necessarily influence the client’s opinion or the compositional outcome. The latter are adept at conception and creative development, but may not fully grasp how to integrate a marketing initiative into the work, much less a brand mandate. Not to mention, understand that highly skilled creative craftsmanship often requires one engage clients at the same time one is focused on development. How do you do that when you’re staring at a screen and your back is to a room full of clients? Maybe you should turn the desk around?

In my own development I sought to straddle the fence: I wanted to be more than an Account Executive or a Project Manager. The earliest and nearest role models available to me were Advertising Agency Producers. Most were a cross between a road manager and a business manager, but the ones I most admired resembled film producers as they collaborated with their directors. They may not have defined either the brand message or initiated any specific commercial storyline, but they were masters at maximizing both marketing and entertainment value from any given project, and once focusing a creative strategy, assumed an executive leadership role in the subsequent production.

How was I going achieve that measure of influence for myself in order to advance my career and fulfill the professional expectations I had for myself?

Well, as music producer, I was often the first contact from the agency for a commission. And as it happened, whenever an agency called, they often wanted to know my initial gut instinct regarding what kind musical score the ad deserved, based on a review of story boards, if only to understand how I was going to develop an estimate. I immediately understood if I could define the creative direction at this early stage, I would be in front of the project from conception to final delivery. Not in front, as assuming or usurping the role of a Creative Director, but at an advantage in the process because, as an idea’s source, I possessed a comprehensive overview of it, and therefore could have an authoritative voice in its development.

In the early days I took these calls with our superbly talented Creative Director, Alexander Lasarenko, and at the time I always deferred to his expertise. But on the occasions when he wasn’t available, or perhaps when he was testing me, I would find myself alone on the call with the client and the direction was left to my sole discretion. In the beginning I winged it, and to be honest, half the time I was frightened. And as you can imagine I didn’t always bat a hundred.

However, eventually my ear and eyes connected and I became an expert at concepting interesting creative directions –based on initial preproduction storyboard review– that both enhanced the story, and/or fulfilled the marketing solutions required by the project at hand (Later I would also develop an understanding of how to incorporate brand message into the work).

By the way, another outcome of defining audio direction, is the potential to influence not just the sound score, but how the final commercial was going to be shot to some degree, and certainly how it was edited.

That's a lot of power for a music guy: The client may only be paying you five or ten percent of the his or her overall production budget, but by defining audio direction and delivering a temp track or sketch before the shoot, you've just put yourself in the position of influencing the entire project, and therefore every dollar spent on its development. By the time the first edit is sent your way, you are basically done with the heavy lifting.

Elias proved a great training ground. And later, after I left the company, I had a two year string of amazing successes with another company when it seemed like every idea I pitched went straight to air without revision.

Either way, you can bet that much of that success came not just from my own contributions, but from having been fortunate to choose adept creative partners as collaborators in all those projects. There have been times in my life as an artist or producer that I struggled alone, but in those days I was surrounded by smart, world class collaborators at every turn.

One such talent was Todd Schietroma, a composer/percussionist I recruited. Todd often came to the table with a million concepts for any given storyboard. Of course, I always loved it when my own ideas were chosen for development, but we were lucky if any of us presented an idea that pulled in a high profile project.

The bottom line: Analyze each board or rough cut that comes your way, and then bend your brain in such a manner that you get in the habit of giving birth to new, inventive ideas and creative solutions for any given commission.

The alternative is that someone else will provide you with a directive that you will merely execute and project manage. That's not such a bad thing when you work as a team, but it does make VIP client management easier when you are a creator or co-creator, and not just an administrator.

Keep in mind also, that as a producer, if your pitch goes into production –then it’s likely you have a much easier time budgeting the project.

It also means that when you deliver the concept in the form of a creative brief to the Creative Department to manage its development, you will also have some idea of how development should proceed, at what rate, and how to manage your time and budget. It may not actually make you the Creative Director, but it will make you fully vested in a comprehensive creative development.

In a nutshell, being first to concept –defining direction– is one strategic way any creative producer can stay ahead of a given project. At the very least, it certainly helps one identify appropriate resources, track creative development, and control of cost and schedule.

And that should almost be the first rule anyone in any kind of media production learns.

It's how interns become Senior Producers, for sure.

The former excel at managing clients and sometimes process, but do not necessarily influence the client’s opinion or the compositional outcome. The latter are adept at conception and creative development, but may not fully grasp how to integrate a marketing initiative into the work, much less a brand mandate. Not to mention, understand that highly skilled creative craftsmanship often requires one engage clients at the same time one is focused on development. How do you do that when you’re staring at a screen and your back is to a room full of clients? Maybe you should turn the desk around?

In my own development I sought to straddle the fence: I wanted to be more than an Account Executive or a Project Manager. The earliest and nearest role models available to me were Advertising Agency Producers. Most were a cross between a road manager and a business manager, but the ones I most admired resembled film producers as they collaborated with their directors. They may not have defined either the brand message or initiated any specific commercial storyline, but they were masters at maximizing both marketing and entertainment value from any given project, and once focusing a creative strategy, assumed an executive leadership role in the subsequent production.

How was I going achieve that measure of influence for myself in order to advance my career and fulfill the professional expectations I had for myself?

Well, as music producer, I was often the first contact from the agency for a commission. And as it happened, whenever an agency called, they often wanted to know my initial gut instinct regarding what kind musical score the ad deserved, based on a review of story boards, if only to understand how I was going to develop an estimate. I immediately understood if I could define the creative direction at this early stage, I would be in front of the project from conception to final delivery. Not in front, as assuming or usurping the role of a Creative Director, but at an advantage in the process because, as an idea’s source, I possessed a comprehensive overview of it, and therefore could have an authoritative voice in its development.

In the early days I took these calls with our superbly talented Creative Director, Alexander Lasarenko, and at the time I always deferred to his expertise. But on the occasions when he wasn’t available, or perhaps when he was testing me, I would find myself alone on the call with the client and the direction was left to my sole discretion. In the beginning I winged it, and to be honest, half the time I was frightened. And as you can imagine I didn’t always bat a hundred.

However, eventually my ear and eyes connected and I became an expert at concepting interesting creative directions –based on initial preproduction storyboard review– that both enhanced the story, and/or fulfilled the marketing solutions required by the project at hand (Later I would also develop an understanding of how to incorporate brand message into the work).

By the way, another outcome of defining audio direction, is the potential to influence not just the sound score, but how the final commercial was going to be shot to some degree, and certainly how it was edited.

That's a lot of power for a music guy: The client may only be paying you five or ten percent of the his or her overall production budget, but by defining audio direction and delivering a temp track or sketch before the shoot, you've just put yourself in the position of influencing the entire project, and therefore every dollar spent on its development. By the time the first edit is sent your way, you are basically done with the heavy lifting.

Elias proved a great training ground. And later, after I left the company, I had a two year string of amazing successes with another company when it seemed like every idea I pitched went straight to air without revision.

Either way, you can bet that much of that success came not just from my own contributions, but from having been fortunate to choose adept creative partners as collaborators in all those projects. There have been times in my life as an artist or producer that I struggled alone, but in those days I was surrounded by smart, world class collaborators at every turn.

One such talent was Todd Schietroma, a composer/percussionist I recruited. Todd often came to the table with a million concepts for any given storyboard. Of course, I always loved it when my own ideas were chosen for development, but we were lucky if any of us presented an idea that pulled in a high profile project.

The bottom line: Analyze each board or rough cut that comes your way, and then bend your brain in such a manner that you get in the habit of giving birth to new, inventive ideas and creative solutions for any given commission.

The alternative is that someone else will provide you with a directive that you will merely execute and project manage. That's not such a bad thing when you work as a team, but it does make VIP client management easier when you are a creator or co-creator, and not just an administrator.

Keep in mind also, that as a producer, if your pitch goes into production –then it’s likely you have a much easier time budgeting the project.

It also means that when you deliver the concept in the form of a creative brief to the Creative Department to manage its development, you will also have some idea of how development should proceed, at what rate, and how to manage your time and budget. It may not actually make you the Creative Director, but it will make you fully vested in a comprehensive creative development.

In a nutshell, being first to concept –defining direction– is one strategic way any creative producer can stay ahead of a given project. At the very least, it certainly helps one identify appropriate resources, track creative development, and control of cost and schedule.

And that should almost be the first rule anyone in any kind of media production learns.

It's how interns become Senior Producers, for sure.

Friday, June 08, 2001

How to Build a Creative Team

With Jonathan Elias heading out west, and myself having made the transition from arts and office administrator to music producer, Scott Elias commissioned Alexander Lasarenko, our talented Creative Director, and myself to keep New York’s three studios operational. Our mission was two fold: staff up the studios with new talent and get work. In fact, we were told we had a year to demonstrate Billings that merited keeping the doors open, or we’d both be out of our jobs.

It was scary and but I was also excited. And Alex and I shared a common desire to create an altogether different culture than the one that preceded us, and I think we both jumped at the opportunity to put our own personal stamps on what was already a legacy company. I certainly loved the organization to such an extent that I conducted myself as though I owned it, and at least a couple of clients, it turned out, haha, seemed to think I did. But I think anytime you find a really successful company, you’ll find its employees all feel personally vested in its success.

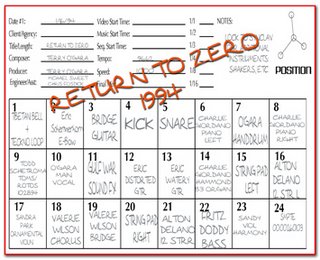

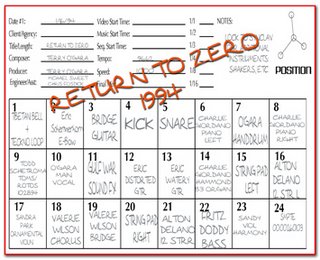

By 1993 or 1994, however, after a series of departures, the composition staff had dwindled down to two ‘night guys’. One was Fritz Doddy, a musical chameleon who came highly recommended by Doug Hall, but whose demo had nevertheless languished in a shoe box before I heard it and then spent the next six months championing his talent to my superiors. 'How long will it take before you hire this guy?' I wondered. But then, in my own case, I had first approached the company 4 years before they hired me, and then they only hired me after a solid campaign where I called the company every single day for six months.

Fritz himself had also already made several overtures to the creative department, but there were so many exceptional talents besides him that were also beating down our doors that anyone who was eventually hired there really required someone inside to evangelize their talents on their behalf. For me, it was Audrey Arbeeny, Hugh Barton, Sherman Foote, and Ray Foote who eventually brought me in.

In addition to Fritz Doddy, the other senior composer was even newer hire named Alton Brammer Delano. Alton was an inspirational and eclectic ahead-of-his-time composer–cum–sound designer that had come to Ray's attention by scoring the 1992 MTV Video Music Awards, and then despite his obvious upward trajectory, still agreed to start out as a studio assistant simply in order to get his foot in the door. That's how desirable a staff composer job at Elias was in those days (and may still be).

By 1993 or 1994, however, after a series of departures, the composition staff had dwindled down to two ‘night guys’. One was Fritz Doddy, a musical chameleon who came highly recommended by Doug Hall, but whose demo had nevertheless languished in a shoe box before I heard it and then spent the next six months championing his talent to my superiors. 'How long will it take before you hire this guy?' I wondered. But then, in my own case, I had first approached the company 4 years before they hired me, and then they only hired me after a solid campaign where I called the company every single day for six months.

Fritz himself had also already made several overtures to the creative department, but there were so many exceptional talents besides him that were also beating down our doors that anyone who was eventually hired there really required someone inside to evangelize their talents on their behalf. For me, it was Audrey Arbeeny, Hugh Barton, Sherman Foote, and Ray Foote who eventually brought me in.

In addition to Fritz Doddy, the other senior composer was even newer hire named Alton Brammer Delano. Alton was an inspirational and eclectic ahead-of-his-time composer–cum–sound designer that had come to Ray's attention by scoring the 1992 MTV Video Music Awards, and then despite his obvious upward trajectory, still agreed to start out as a studio assistant simply in order to get his foot in the door. That's how desirable a staff composer job at Elias was in those days (and may still be).

A year later, Alton Delano and Fritz Doddy had formed a powerful musical partnership, combining two trends at the time, grunge rock and liturgical loops, and which Alex then synched to found footage of dolphins in the wild, of all things, and to such great effect, that it actually earned us several projects.

Another important part of the new configuration was Michael Sweet, who not only being one of Jonathan’s engineers was also an early creative technologist. And after Jonathan’s departure for LA, Michael’s role shifted to a lead interactive audio role, which put him in the position of an audio pioneer in those days.

To our core team we added a very effective sales rep, Debbie Maniscalco, with whom I collaborated on closing an astounding amount of sales over the next two years. In the music production community, a sales rep solicits projects from advertising agencies and film directors. The job requires the combined skill set of a socialite and a Soviet era Super Spy. That is, combined talents for people and analytics. Debbie was incredibly resourceful in this regard. Together we formed one of the most satisfying business partnerships of my career.

With the studio’s namesake, Jonathan Elias, now operating out of Los Angeles, however, the New York office required some kind of draw to separate us from our competitors, which now, ironically, included our own west coast office. So, Alex commissioned me with identifying promising young talent that we might develop into the new music stars of the advertising community. Who or what this talent should be, and how these talents would fit within the organization was not yet determined. So, apart from learning how to produce projects, I also had to learn how to manage a production company; promote its services; and recruit creative professionals, or young people who could develop into them.

Alex and I never sat down and made a plan; we simply trusted the other in the responsibilities assigned to them. And as team building goes, I actually did have a few specific ideas about how I wanted to accomplish this task.

The model I inherited from my predecessors was built on staffing each studio with a Synclavier Operator, essentially an electronic musician who works a recording studio in an equivalent way that many composers today construct music entirely by themselves using a laptop and sample libraries. It may be a successful model, but I had also observed that individual composers working separately often felt pitted against each other in competition for every project that came through the studio’s doors.

To our core team we added a very effective sales rep, Debbie Maniscalco, with whom I collaborated on closing an astounding amount of sales over the next two years. In the music production community, a sales rep solicits projects from advertising agencies and film directors. The job requires the combined skill set of a socialite and a Soviet era Super Spy. That is, combined talents for people and analytics. Debbie was incredibly resourceful in this regard. Together we formed one of the most satisfying business partnerships of my career.

With the studio’s namesake, Jonathan Elias, now operating out of Los Angeles, however, the New York office required some kind of draw to separate us from our competitors, which now, ironically, included our own west coast office. So, Alex commissioned me with identifying promising young talent that we might develop into the new music stars of the advertising community. Who or what this talent should be, and how these talents would fit within the organization was not yet determined. So, apart from learning how to produce projects, I also had to learn how to manage a production company; promote its services; and recruit creative professionals, or young people who could develop into them.

Alex and I never sat down and made a plan; we simply trusted the other in the responsibilities assigned to them. And as team building goes, I actually did have a few specific ideas about how I wanted to accomplish this task.

The model I inherited from my predecessors was built on staffing each studio with a Synclavier Operator, essentially an electronic musician who works a recording studio in an equivalent way that many composers today construct music entirely by themselves using a laptop and sample libraries. It may be a successful model, but I had also observed that individual composers working separately often felt pitted against each other in competition for every project that came through the studio’s doors.

And I also noticed how composers sometimes took an adversarial stance with clients over small creative points; the idea as it was explained to me was that clients don't always know what they want, so you have to fight for great music. Unfortunately, some clients did not appreciate losing fights to the people they had hired.

So how might we change the model in a way that benefited our culture, our composers, and our clients?

Long before I heard the phrase 'strategic relationships', it was obvious to me that an ensemble of contrasting skill sets groomed to embrace collaborative partnerships –not competitors– would yield the maximum benefit to both the company and its many creative endeavors.

I'm sure I gained this ensemble mentality from my training as dancer. (I received a BFA in dance from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts). A dance company is, after all, a team of individual performing artists working together to present a simultaneously singular and collaborative work of art.

And if one looked at the entire production of a TV commercial, from storyboard to shoot to edit, score and finish –one easily saw it as a work of art executed by a team. So, within that, why couldn't the audio development process work the same way?

Consider the way a band or orchestra work together. In a band, ideally, each member simultaneously contains uniquely contrasting and complimentary gifts. That's how it should work, I thought. In a symphony, the french horns play with the violins; they aren't allowed to play whatever they want –which is the way our music company seemed to work, with individual craftsmen following their own muse quite apart from what anyone else was doing.

In short, I envisioned a team of collaborating composers, each with a distinct and different musical or technical ability.

I placed pre-Internet ads in the New York Times and The Village Voice and received about 300 resumes. I met about 30 candidates and culled those by half, introducing the most promising artists to Alex, Fritz and Alton. We hired several young people who appealed to the consensus. Among them: Matt Fletcher, a technologist who came to us from NYU’s music department; Kerry Smith, a rock guitar player who had been paying his bills by working at Kinko’s; Todd Schietroma, a conservatory trained master percussionist from Texas; GianCarlo Libertino, a classical guitarist who would go on win a small amount of fame whistling the theme for Comedy Central; and Mario Piazza, an engineer/composer whom I recruited from New York's legendary Hit Factory.

Add to this in leadership roles, Fritz Doddy's immense skills as a multi-instrumentalist, Alton Delano's uniquely impressionistic approach to music and sound design, and Alex Lasarenko's mastery of traditional symphonic scoring, and there wasn't much now that we couldn't collectively accomplish in house, especially if we all worked together towards a common goal.

There were several others –many others, actually– who also came along for the ride, if only briefly. (In the end, I was one of those, too, who hopped on and off the machine.) Whether they left for other careers or studios, had girlfriends or boyfriends on the west coast, or had family obligations, or were let go for one reason or another, there are still some whose contributions continue to inspire me and my own creative work. To mention just three, there were several young women –Jennifer McGee, Erika Horsey and Lane Lenhart– who were all hired as studio assistants, and who were all so particularly talented, that it would not surprise me to see any if their names surface on the national stage sometime in the future.

All in all, I sought recruits who not only possessed a distinct talent for composition, but who also demonstrated themselves as gifted musicians with little or no overlap in skill sets. This forced collaboration, and that was an important factor in creating a vibrant organizational culture in a creative industry. Further, I not only selected contrasting skill sets, but contrasting personalities, -we weren’t just hiring staffers, we were hiring talent to groom into industry stars and musical brands. Once hired, I thereafter impressed upon each the importance that every member contribute to each others' projects. My idea was to transform the culture of internal competition into a team effort striving for exceptionally high standard of creative excellence. I felt most proud, not necessarily when we won a new client, but when walking past the studios I noticed the composers working together in each others rooms.

Competition with one's external competitors, or even between divisions in one large company, may be productive, but in a boutique artistic climate, I think internal collaboration yields greater rewards for all, and improves both morale and the bottom line. Indeed, I think the best way to consider this formula is to insure internal collaborations are so efficient that they win external competitions.

To this end, I also attempted to create an environment where creatives did not feel like the necessity to keep 'trade secrets' from one another. Naturally, I didn't do it alone; Alex, Alton and Fritz all wanted to achieve the same ends. But Elias had long been a top down highly political organization, and it was difficult to initiate change from the creative side, especially since the composers were all essentially new employees. So, it really fell to production to challenge legacy processes and I did my best.

Each new composer/musician was expected to share their craft with the others. Their personal reward for contributing to an open work environment would be the knowledge returned to them when they learn something from his or her colleagues' own specialties. For instance a classically trained artist would learn studio processes and mixing techniques from someone more electronically inclined, than if they forged ahead in isolation (as I did on my own journey). Conversely, the technologists in the lot would find themselves improving their musicianship by working with traditional musicians.

Happily, this new paradigm for the company also proved an advantageous defense against the ongoing recession. Now, instead of hiring session musicians to simply bring to life synthesized tracks produced by engineers and electronic musicians, our new musically diverse staff, while professionally inexperienced, nevertheless possessed the talent (and enthusiasm) to enhance each other's compositions –from concept to console– and all in-house, thereby cutting production costs and talent expenditures significantly.

In fact, at the same time I was building a creative team, my boss, Scott Elias, had also commissioned me to cut production costs by 20%, and I actually accomplished that by simply by hiring people who would work together!

So, how do you build a creative team? My answer circa 1993 - 1994 was to recruit the most talented people I could identify, and to insure that their talents aside, that they were also well liked by at least three other colleagues in the organization; and who relative to one another simultaneously represented Contrasting and Complimentary skill sets. And then, after they were hired, I worked very hard to cultivate in them a desire for working together in an open, collaborative environment, to convey the idea that this had always been the case in this organization, and to protect them from any influence that suggested otherwise. -that while the tracks may be in competition with each other, the people were not.

It was a great big experiment, actually, but it succeeded, and in the end, that team of music and sound design talents turned out to be one of the longest running, highest earning and cohesive creative teams in the history of the company.

I'm sure I gained this ensemble mentality from my training as dancer. (I received a BFA in dance from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts). A dance company is, after all, a team of individual performing artists working together to present a simultaneously singular and collaborative work of art.

And if one looked at the entire production of a TV commercial, from storyboard to shoot to edit, score and finish –one easily saw it as a work of art executed by a team. So, within that, why couldn't the audio development process work the same way?

Consider the way a band or orchestra work together. In a band, ideally, each member simultaneously contains uniquely contrasting and complimentary gifts. That's how it should work, I thought. In a symphony, the french horns play with the violins; they aren't allowed to play whatever they want –which is the way our music company seemed to work, with individual craftsmen following their own muse quite apart from what anyone else was doing.

In short, I envisioned a team of collaborating composers, each with a distinct and different musical or technical ability.

I placed pre-Internet ads in the New York Times and The Village Voice and received about 300 resumes. I met about 30 candidates and culled those by half, introducing the most promising artists to Alex, Fritz and Alton. We hired several young people who appealed to the consensus. Among them: Matt Fletcher, a technologist who came to us from NYU’s music department; Kerry Smith, a rock guitar player who had been paying his bills by working at Kinko’s; Todd Schietroma, a conservatory trained master percussionist from Texas; GianCarlo Libertino, a classical guitarist who would go on win a small amount of fame whistling the theme for Comedy Central; and Mario Piazza, an engineer/composer whom I recruited from New York's legendary Hit Factory.

Add to this in leadership roles, Fritz Doddy's immense skills as a multi-instrumentalist, Alton Delano's uniquely impressionistic approach to music and sound design, and Alex Lasarenko's mastery of traditional symphonic scoring, and there wasn't much now that we couldn't collectively accomplish in house, especially if we all worked together towards a common goal.

There were several others –many others, actually– who also came along for the ride, if only briefly. (In the end, I was one of those, too, who hopped on and off the machine.) Whether they left for other careers or studios, had girlfriends or boyfriends on the west coast, or had family obligations, or were let go for one reason or another, there are still some whose contributions continue to inspire me and my own creative work. To mention just three, there were several young women –Jennifer McGee, Erika Horsey and Lane Lenhart– who were all hired as studio assistants, and who were all so particularly talented, that it would not surprise me to see any if their names surface on the national stage sometime in the future.

All in all, I sought recruits who not only possessed a distinct talent for composition, but who also demonstrated themselves as gifted musicians with little or no overlap in skill sets. This forced collaboration, and that was an important factor in creating a vibrant organizational culture in a creative industry. Further, I not only selected contrasting skill sets, but contrasting personalities, -we weren’t just hiring staffers, we were hiring talent to groom into industry stars and musical brands. Once hired, I thereafter impressed upon each the importance that every member contribute to each others' projects. My idea was to transform the culture of internal competition into a team effort striving for exceptionally high standard of creative excellence. I felt most proud, not necessarily when we won a new client, but when walking past the studios I noticed the composers working together in each others rooms.

Competition with one's external competitors, or even between divisions in one large company, may be productive, but in a boutique artistic climate, I think internal collaboration yields greater rewards for all, and improves both morale and the bottom line. Indeed, I think the best way to consider this formula is to insure internal collaborations are so efficient that they win external competitions.

To this end, I also attempted to create an environment where creatives did not feel like the necessity to keep 'trade secrets' from one another. Naturally, I didn't do it alone; Alex, Alton and Fritz all wanted to achieve the same ends. But Elias had long been a top down highly political organization, and it was difficult to initiate change from the creative side, especially since the composers were all essentially new employees. So, it really fell to production to challenge legacy processes and I did my best.

Each new composer/musician was expected to share their craft with the others. Their personal reward for contributing to an open work environment would be the knowledge returned to them when they learn something from his or her colleagues' own specialties. For instance a classically trained artist would learn studio processes and mixing techniques from someone more electronically inclined, than if they forged ahead in isolation (as I did on my own journey). Conversely, the technologists in the lot would find themselves improving their musicianship by working with traditional musicians.

Happily, this new paradigm for the company also proved an advantageous defense against the ongoing recession. Now, instead of hiring session musicians to simply bring to life synthesized tracks produced by engineers and electronic musicians, our new musically diverse staff, while professionally inexperienced, nevertheless possessed the talent (and enthusiasm) to enhance each other's compositions –from concept to console– and all in-house, thereby cutting production costs and talent expenditures significantly.

In fact, at the same time I was building a creative team, my boss, Scott Elias, had also commissioned me to cut production costs by 20%, and I actually accomplished that by simply by hiring people who would work together!

So, how do you build a creative team? My answer circa 1993 - 1994 was to recruit the most talented people I could identify, and to insure that their talents aside, that they were also well liked by at least three other colleagues in the organization; and who relative to one another simultaneously represented Contrasting and Complimentary skill sets. And then, after they were hired, I worked very hard to cultivate in them a desire for working together in an open, collaborative environment, to convey the idea that this had always been the case in this organization, and to protect them from any influence that suggested otherwise. -that while the tracks may be in competition with each other, the people were not.

It was a great big experiment, actually, but it succeeded, and in the end, that team of music and sound design talents turned out to be one of the longest running, highest earning and cohesive creative teams in the history of the company.

Thursday, June 07, 2001

Six Sigma Music Producer

I arrived at the Elias studios on the third floor of 6 West 20th with a global perspective courtesy a childhood spent abroad, and modest but then eclectic musical talent because it included both a classical and electronic musical background.

Two years later, Scott Elias promoted me to Senior Producer, but I was still a novice with a bigger job title than skill set and lacked a production mentor at a critical time in my professional development. Six months before, the production department had disbanded when its several members left to start or join competing companies. How was I going to manage what had once been the responsibility of a department?

In short order, I had to quickly find a way how to manage national broadcast music and sound design projects without embarrassing myself or the company I worked for.

When I eventually found myself with two large three-ring binders full of organized notes, I called the resulting compendium ‘The Production Manual’, and with it I established a personal and practical foundation and reference for the production of music, sound design and sonic branding. As I evolved, the Production Manual evolved. And by the time I resigned from Elias Arts (then called Elias Associates), all those once complicated or difficult lessons had become second nature. Not to mention that protocols I developed had been adopted throughout both of our offices in New York and Los Angeles, and continued to support the organization for some time thereafter.

I would suggest any novice producer do the same as I did; a sentence or two every day is enough: who did I work for, what did I do, what did I accomplish, what did I learn? What went right? What went wrong? Is there a process?

If you can manage it, your production manual will also serve as a collection of the legal and business paperwork you receive from clients that can be used as boiler plate documents for future projects, and commonly referenced items, such as basic union rules governing the hiring of musicians and singers.

What else goes into the professional journal? The project specifications, the creative brief, a list of internal and external personnel and a post-mortem –essentially a synopsis of how the project concluded, problems or obstacles and how they were resolved, and lessons learned.

What gets saved to your computer? Every single digital document and electronic communication regarding the project, from both internal and external sources.

Sound like a lot of information to keep? It is, and you'll be adding to its volume for the length of your entire career.

Did you notice I haven't mentioned anything about music? If you're just getting started, I recommend another notebook altogether which you can use to keep notes on actual studio production.

In essence, you're writing two text books as you proceed: one is on the business of music production, and the other is for tracking your creative and technical development. And by the time you retire, you may finally know just enough to actually do your job without referencing any of your notes. Bonus points if you also can share this knowledge with others you meet who want to walk down the same path you did.

* * *

By the way, if you really have no experience producing music at all, I recommend buying and beginning with Propellerhead Software's music production program REASON. It's the closest thing I know that teaches traditional studio signal path. What that is and why that's important would probably sound nonsensical to you right now, but in lieu of interning in a recording studio, REASON is as good a place as any to start.

Two years later, Scott Elias promoted me to Senior Producer, but I was still a novice with a bigger job title than skill set and lacked a production mentor at a critical time in my professional development. Six months before, the production department had disbanded when its several members left to start or join competing companies. How was I going to manage what had once been the responsibility of a department?

In short order, I had to quickly find a way how to manage national broadcast music and sound design projects without embarrassing myself or the company I worked for.

Anyone of any skill level can call themselves a producer. But in the world I inhabited, a producer was the first and primary point of contact between representatives of a Fortune 500 brand, a global advertising company, or a film studio, -and also the person who translated those incoming business or communications problems into creative assignments. And those people -the clients and the creatives- were generally seasoned and experienced experts with little patience for people who were not.

So, how did I level up? By the time I became a producer I certainly understood professional music production, but I was extremely deficit on two fronts:

1) Being green and an introvert, I was often intimidated by people I perceived as important.

2) Being a producer at a commercial production facility requires not just an understanding of music theory or audio gear, but a comprehensive understanding of intellectual property law and film production.

So, how did I level up? By the time I became a producer I certainly understood professional music production, but I was extremely deficit on two fronts:

1) Being green and an introvert, I was often intimidated by people I perceived as important.

2) Being a producer at a commercial production facility requires not just an understanding of music theory or audio gear, but a comprehensive understanding of intellectual property law and film production.

I still recall managing my first recording session and having to work up the courage just to nudge the famous record producer and recording engineer, -Josh Abbey- that he had 15 minutes to wrap a mix. He turned his head, and gently swatted me away like a fly on a hot summer day.

Well, I knew I had to get over treating important people like important people if I was going to get anywhere. I had to see them as ‘us’, and realize we were working together for a common purpose, and for our mutual benefit.

Well, I knew I had to get over treating important people like important people if I was going to get anywhere. I had to see them as ‘us’, and realize we were working together for a common purpose, and for our mutual benefit.

I also needed to become as good at my job as our clients and creatives were at there jobs.

It was a tall order. I had to become a knowledge expert and be able to comfortably talk shop with advertising executives, brand strategists, lawyers, film directors, editors, composers, famous actors, musicians and singers (and later, game developers and software engineers, too). It wasn’t easy, but I wasn’t the first producer in the world, -other done producers had done it. In fact, all producers do it. Not to mention that working for a busy facility meant I had many role models among our clients, partners and colleagues. So, it was a solvable problem, and this is how I did it:

First, in order to advance my understanding of how a music or sound design project is managed, I scoured archived boxes of job folders and studied every single job for the four or five years prior to my appointment. I reviewed whatever creative specifications might be still be available; I then compared the brief to bids; and compared the bids to contracts, invoices, AFM, AFTRA & SAG contracts. As a tandem exercise, I followed the paper trail with digital audio and Video Recordings from demo to final. In this way, I learned a great deal about the production of all variety of commercial audio projects.

In short, I learned to connect the dots between the creative and the business.

What the documentation did not reveal, however, was how one arrived at a specific creative direction; nor did they provide illumination regarding the psychology of audio on specific demographics; nor did they so much as mention how a communications mandate might be filtered through a brand strategy in order to inform an assignment in sonic branding. I learned those things by way of actual experience, on actual jobs and working alongside people who were experts in their respective fields, and whom I was fortunate to have access to. In this regard, Alex Lasarenko provided me with an excellent education in film music and aesthetics, and played a significant role connecting my ears to my eyes. I already had a long-standing interest in semiotics, but Scott Elias and Audrey Arbeeny helped transform my thinking from towards a brand mentality. I'll write about this development in another post.

As for management: I have to tell you, nothing scared this novice producer more than suddenly finding himself in the position of leading a project for which a monolithic brand has paid a very dear amount to broadcast on the Superbowl.

If only there was a text book I could have referred to learn music and post production management. But since I didn’t know of any, I wrote my own. And I did this by cobbling every little bit of advice I received until I could systemize my own set of Standard Operating Procedures for the production and direction of creative projects (music, sound design and sonic branding for a variety of platforms).

In short, I learned to connect the dots between the creative and the business.

What the documentation did not reveal, however, was how one arrived at a specific creative direction; nor did they provide illumination regarding the psychology of audio on specific demographics; nor did they so much as mention how a communications mandate might be filtered through a brand strategy in order to inform an assignment in sonic branding. I learned those things by way of actual experience, on actual jobs and working alongside people who were experts in their respective fields, and whom I was fortunate to have access to. In this regard, Alex Lasarenko provided me with an excellent education in film music and aesthetics, and played a significant role connecting my ears to my eyes. I already had a long-standing interest in semiotics, but Scott Elias and Audrey Arbeeny helped transform my thinking from towards a brand mentality. I'll write about this development in another post.

As for management: I have to tell you, nothing scared this novice producer more than suddenly finding himself in the position of leading a project for which a monolithic brand has paid a very dear amount to broadcast on the Superbowl.

If only there was a text book I could have referred to learn music and post production management. But since I didn’t know of any, I wrote my own. And I did this by cobbling every little bit of advice I received until I could systemize my own set of Standard Operating Procedures for the production and direction of creative projects (music, sound design and sonic branding for a variety of platforms).

It helped, I must confess, that I had already gathered the basic tenants of project management from my father who was a project manager for General Electric, and who had managed the construction of Desalinzation plants, Power Plants and energy facilities around the world. As a result I like to think of myself as the world’s first music producer to understand Critical Path method, and I utilized (an albeit distilled version of) Six Sigma as my mantra in the pursuit of creative excellence, -that is, I made every attempt to minimize imperfections. Suffice to say I had a professional project manager mentality even if I hadn't all the skills and experience of a music producer just yet.

When I eventually found myself with two large three-ring binders full of organized notes, I called the resulting compendium ‘The Production Manual’, and with it I established a personal and practical foundation and reference for the production of music, sound design and sonic branding. As I evolved, the Production Manual evolved. And by the time I resigned from Elias Arts (then called Elias Associates), all those once complicated or difficult lessons had become second nature. Not to mention that protocols I developed had been adopted throughout both of our offices in New York and Los Angeles, and continued to support the organization for some time thereafter.

I would suggest any novice producer do the same as I did; a sentence or two every day is enough: who did I work for, what did I do, what did I accomplish, what did I learn? What went right? What went wrong? Is there a process?

If you can manage it, your production manual will also serve as a collection of the legal and business paperwork you receive from clients that can be used as boiler plate documents for future projects, and commonly referenced items, such as basic union rules governing the hiring of musicians and singers.