When I was three or four years old, my father, James O'Gara, got a job in Saudi Arabia, where he became a close associate of Prince Mohamed Al Faisal, then the head of the Saudi Water company. My dad was in charge of building the first sea water desalinization plant in Saudi. I still remember visiting the construction site, where the desert literally meets the sea, and seeing camels walking among bulldozers, tractors and other equipment.

In fact, our home sat on what was once the eastern perimeter of

Jeddah, on Khalidibm Al-Walid street in the Sharifia district, and abutted the edge of the open desert. However, in the intervening years Jeddah has experienced so much growth that the same plot of land I used to call my backyard now sits squarely in the center of the city.

Whereas now that house is surrounded by a dense metropolitan development, at the time it sat next to an empty sand. The land to back of of our house stretched out to the blue horizon, and next door, quite often, Bedouin would pitch their tents and settle at times with their families.

Whenever the tents went up, I used to go play with the Bedouin kids. One of the games we played was called '

Death to the Infidels'. Death to the Infidels is the Islamic equivalent to Cowboys and Indians, except that, technically speaking,

I am an infidel, something I didn't realize when I ran along the dirt branding a wooden sword or pocket knife.

It's in Saudi that I have my earliest memories of Television. This during a time when Television was pre-cable, pre-satellite, black and white, analog and mono. But I recall watching performances by

Fairuz and

Om Kalthoum, famous Divas, Lebanese and Egyptian, respectively, and their music abounded with depth and color.

Om Kalthoum spins out classical Arabic poems that emerge from her lips like cobwebs of sound. When she sings, words are transformed into transparent math and honey.

However, as we are living in the Royal Kingdom, the only images I have ever seen of Om Kalthoum at that point, capture her wearing a black abaya. To this day, when I picture the singer in my mind’s eye, I do not see a chic Egyptian woman dressed as she might be for the western stage; I see black fabric draped around a microphone.

But what I remember most, what I can hear still, is

adhan (also 'azan', 'athan'), the daily calls to Islamic prayer which were (and I imagine still are) broadcast over roof tops and through the city streets and alleys five times a day.

Then, if the programmers at Saudi Television were feeling especially Christian, perhaps they might afterwards air an intermittent episode of

Lassie.

And so because one could never tell when Lassie might air, I would sit and watch Islamic programming (for what seemed like forever), waiting, waiting for just a few moments with Lassie.

One wonders now just what effect the combination of Lassie and Adhan had on the young, developing brain.

In fact, in those first six years of my life, I had lived in the Caribbean, South America and the mid east. In all that time I heard very little western music beyond the nursery rhymes my mother sang to me. Which is to say, that at the same time my brain was trying to make sense of Mother Goose, I was also assimilating

Calypso,

Huayño, and microtonal Arabic scales.

But, at the time, it all seemed ordinary to me. I think that's because in my so-far short life, I had not lived long enough in anyone place for anyone music to sound anything other than normal and ordinary. Live in any one place long enough, and art gets embedded, even frozen into the culture, not simply because it belongs in one place or another, but because that's where you assign it.

On the other hand, keep moving, so the only thing constant is change, and human culture converges so that Arabic violin music, Bach, Afro-Caribbean grooves and Hollywood TV scores come to represent equal but different elements along a sonic continuum.

And that's also why I have always associated Barry White with Puerto Rico, because that's where I first heard his music, pouring out of the windows of teenager's cars and little cinder block houses while I was running around the streets of La Rambla, trying to avoid predatory packs of stray dogs.

If you're lucky like that, the brain will build bridges connecting what some might consider disparate sounds but to a traveler (or a child) they sound neither strange nor foreign, but actually quite comforting.

Which is not to say, that I accepted and liked everything I heard.

As it happens, my older brother and sister turned me onto Rock'n'Roll, at the same time I was living in the Mideast. And let me tell you, the first time I heard it, I didn't like it one bit.

Both were teenagers attended boarding school in the United States. So, naturally, I was excited when they came to Saudi to visit us at Christmas. In order to survive a few weeks overseas, my brother brought with him

The Doors, and my sister brought with her

Bob Dylan and

The Beatles.

Today, classic rock is considered so innocuous and it is often played to and for children, who also seem to like it. But that was not the case in the years which this music was first emerging. It was then thought to be radical, noisy and dangerous, and it was.

No surprise then that upon entering the country, the Saudi authorities confiscated some of my brothers tapes (and shortly thereafter those tunes started to be heard on local radio... coincidence?)

Anyway, to this day I remember sitting on the floor with my Legos, being no more than five years old, and for the first time in my life I was conscious that I was listening to something called American rock'n'roll (not to mention at the peak of its golden age!).

And I recall thinking in not exactly these words:

"What is this crap?"

Because, it was obvious to me –not The Beatles, not the Doors, not Bob Bylan– there was simply nothing in this American music that compared to the Islamic call for afternoon prayer, broadcast live from Mecca.

I spent three months in Vermont studying dual compositional studies. Firstly, I had been drawn up there to study computer music programming with a pioneer in the field, Joel Chadabe, via my readings of MIT's Computer Music Journal. It was Joel who sent me off to work for Jonathan Elias –another previous student of his– with his gracious recommendation.

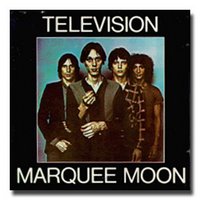

I spent three months in Vermont studying dual compositional studies. Firstly, I had been drawn up there to study computer music programming with a pioneer in the field, Joel Chadabe, via my readings of MIT's Computer Music Journal. It was Joel who sent me off to work for Jonathan Elias –another previous student of his– with his gracious recommendation. Later in life, after what seemed a lifetime in a recording studio, I abandoned technology for several years in order to reconnect with the simplicity of steel strings, and studied guitar with Richard Lloyd of the legendary band Television. There are teachers and their are wizards. Richard is a wizard. He imparted on me an idea to think less in terms of linear melodic structure, more like a guitarist –fingers and inner ear surfing a three dimensional diagonal navigation across a pitch/emotion axis.

Later in life, after what seemed a lifetime in a recording studio, I abandoned technology for several years in order to reconnect with the simplicity of steel strings, and studied guitar with Richard Lloyd of the legendary band Television. There are teachers and their are wizards. Richard is a wizard. He imparted on me an idea to think less in terms of linear melodic structure, more like a guitarist –fingers and inner ear surfing a three dimensional diagonal navigation across a pitch/emotion axis.